After the last article, the parts of the Callisto compiler and its ARM64 backend that I’ve covered are enough to start building Callisto code for ARM64, but we still don’t have all the pieces to make that code do anything useful, outside of manually inserting asm blocks.

Because Callisto makes even operations that would be considered primitive in other languages part of the standard library, the next step to adding a backend after getting the compiler itself working is to implement those primitives. The core library is documented on Callisto’s site, and includes basic CPU functionality, as well as some primitive functions to interact with OS features like files and command line arguments.

asm and inline

So how do these low-level primitives look when written in Callisto? Well, there’s a couple of important pieces of syntax to know about. Firstly, we have asm blocks. These insert assembly code directly into the output file wherever they are encountered. So in this function:

func example begin

1 2

asm

"mov x11, #3"

end

+

end

A (pointless) mov instruction will be inserted in the output, between the code to push the values and the code to call +. This will be the key to performing any interesting operations, since it’s the only way to introduce new behaviour into the language.

The other piece of syntax is inline. It works like func, defining a word that can be used elsewhere, but instead of compiling as a real function call, it just inserts the contained code directly into the calling function.

This is especially useful when combined with asm to make reusable assembly blocks, which is the main reason it comes up in the core files. Instead of using a function call for a small snippet of assembly code, we can just use inline to repeatedly insert the same useful snippet into each function that uses it.

Core Selection

In Callisto, these core functions are just regular functions in the standard library, so the relevant source files still need to be included. For most programs, you won’t care about the target platform at all, and you’ll just want the right versions of the core functions to be available.

This is the job of cores/select.cal in the standard library. Depending on the current target platform, it will include different platform-specific core files for you. I’ll update that file first, because it will make it possible to build existing example source code.

###### CPU ######

# ...

version arm64

include "cpu/arm64.cal"

end

# ...

###### OS ######

# ...

version arm64

version Linux

include "os/arm64_linux.cal"

end

end

Near the existing platforms, I inserted a version arm64 block to include cpu/arm64.cal, which needs to be included on all ARM64 platforms, including macOS once it’s supported. Later in the file, I added a nested version block to include os/arm64_linux.cal, but only on ARM64 Linux. Later on, this is where I’ll include the macOS equivalent.

With that out of the way, it’s time to start building the core files themselves!

arm64.cal

The first thing to do in arm64.cal is define some helper words for the rest of the file. The ARM64 architecture is designed around registers, but Callisto is stack-based, so we need a way to move data back and Forth between the two.

This is where the idea of inline from before comes in handy. These are very common operations, but we don’t really want to waste an entire function call on what end up being single-instruction functions, so let’s inline them all:

inline __arm64_pop_x0 begin asm

"ldr x0, [x19, #-8]!"

end end

inline __arm64_pop_x1 begin asm

"ldr x1, [x19, #-8]!"

end end

# ...

inline __arm64_push_x0 begin asm

"str x0, [x19], #8"

end end

inline __arm64_push_x9 begin asm

"str x9, [x19], #8"

end end

# ...

As a quick reminder, x19 is the data stack, ldr xn, [x19, #-8]! will pop a value from the stack into register xn, and str xn, [x19], #8 pushes xn to the stack. There are more functions like this for other registers that are used in the core, but they all look the same.

Another handy inline function is __arm64_memcpy, which implements the same memory copy loop used in the compiler backend a couple of times, and demonstrates how to use the pop functions to take arguments from the stack manually:

# src, dest, len

inline __arm64_memcpy begin

__arm64_pop_x11

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"1:"

"ldrb w12, [x9], #1"

"strb w12, [x10], #1"

"subs x11, x11, #1"

"bne 1b"

end

end

Comparisons

Following the order of the x86_64 core, the first words to implement are =, > and similar. In Callisto, these words need to return either 0 (false), or a value of all 1 bits (true). The x86_64 core achieves this with a conditional jump and pushing those values directly, but I came up with a different approach.

The challenge lies in the fact that ARM64, like many CPUs, uses status flags for comparisons and conditional execution, but Callisto wants every comparison result to live on the stack, as an actual integer value. This isn’t a problem exclusive to Callisto, but for many other languages it’s less of an issue as they can optimise out the need for an actual boolean result, and just go straight from compare to conditional jump.

To solve this, there is an ARM64 instruction named csetm, short for Conditional Set Mask. Given a register and one of the standard ARM condition values, csetm checks the condition, and if it is true, sets all bits in the register to 1, otherwise to 0. In other words, it checks a condition and outputs a perfect Callisto boolean value.

The implementation looks like this, with a cmp followed by csetm (Using the eq condition here, but this varies between the 5 comparison words):

func = begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"cmp x9, x10"

"csetm x9, eq"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

This is the pattern most of the core words will follow – pop some arguments, run custom assembly to calculate something, then push the result. I also mostly use the x9-x11 registers, defined as temporary registers in the ARM64 convention.

Memory Access

Next we have @ and ! (conventional names carried over from Forth), used to load and store from memory addresses. There are also equivalents for each supported data size which on ARM64 means the full set of 8, 16, and 32-bit load/store words, in addition to the full 64-bit ones.

These are pretty simple, using a single ldr or str to perform the actual memory operation:

func @ begin

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"ldr x9, [x9]"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

func ! begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"str x9, [x10]"

end

end

The words for smaller memory values – b@, w@ and d@ and their ! counterparts – use suffixed versions of ldr and str like ldrb to control the data size.

Stack Words

There are only three primitive words for moving data around on the stack in Callisto: dup to duplicate the top element, drop to remove it, and swap to swap the positions of the top two elements. The code here is a little strange, because unlike the other core words, we’re not really calculating anything:

func dup begin

asm

"ldr x9, [x19, #-8]"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

func drop begin asm

"sub x19, x19, #8"

end end

func swap begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

__arm64_push_x10

__arm64_push_x9

end

dupworks by using an instruction almost like the one to pop from the stack, but without the!, so the stack pointer is never updated – we just read from the top of the stack. This can then be pushed as usual.dropdoesn’t need to use the value it removes from the stack at all, so it skips a memory access and goes straight to changing the data stack pointer.swapis the closest to a typical core word, but is entirely pops and pushes, since it just needs to move around values that are already on the stack.

Arithmetic

Next up, let’s do some maths! Callisto has two variants of each arithmetic word. The plain version like + is for unsigned arithmetic, while s+ and friends are used for signed arithmetic. For the first few words, this doesn’t matter at all, as in two’s complement representation the operations are the same.

func + begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"add x9, x9, x10"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

func s+ begin + end

func - begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"sub x9, x9, x10"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

func s- begin - end

func * begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"mul x9, x9, x10"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

func s* begin * end

Multiplication sometimes does need to differentiate between signed and unsigned operations, but this only applies when you need to obtain a result with a larger data size than the input.

Division does care about signed-ness, and so does modulo by extension. For each of these, the ARM64 core really does need two implementations. Division makes sense, just use udiv or sdiv as appropriate:

func / begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"udiv x9, x9, x10"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

func s/ begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"sdiv x9, x9, x10"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

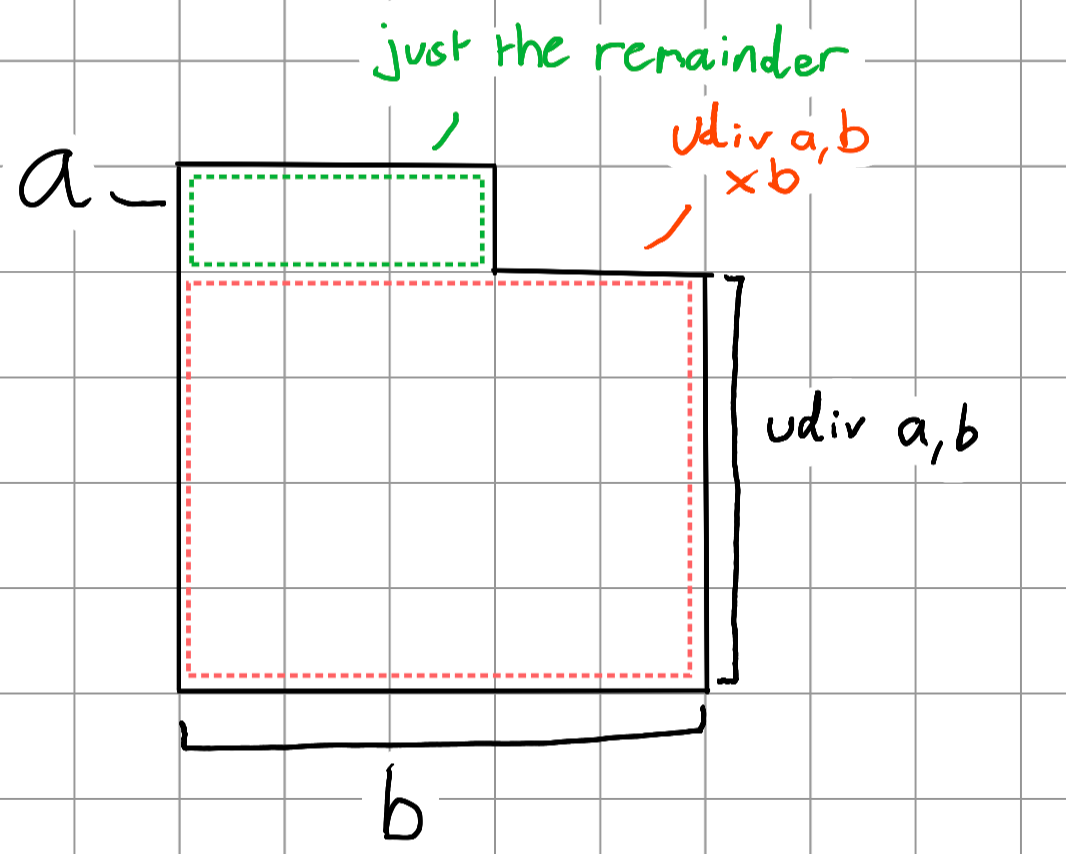

But ARM64 doesn’t have a modulo operation. Instead, we’ll need to build one from (u|s)div. The easiest way to calculate the modulo from the result of dividing a by b is to multiply the result by b, which gives a rounded to a multiple of b, then subtract that from the original a.

I know that might not have been the clearest explanation, so here’s a hopefully useful visual version:

Calculating modulo using `udiv`.

Multiplying and subtracting in this way even has its own ARM64 instruction: msub (Multiply-Subtract). It takes four registers: msub xd, xa, xb, xc, and computes a value in this way: xd = xc - xa * xb, which is exactly what we need for the modulo word.

func % begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"udiv x11, x9, x10"

"msub x9, x11, x10, x9"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

func s% begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"sdiv x11, x9, x10"

"msub x9, x11, x10, x9"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

Bit Operations

The final block of words are all related to bits – and, or, etc., as well as << and >>. Really, there’s nothing new here, we just pop the arguments, use asm to perform the calculation, and push the result, same as ever:

func and begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"and x9, x9, x10"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

# ...

func >> begin

__arm64_pop_x10

__arm64_pop_x9

asm

"lsr x9, x9, x10"

end

__arm64_push_x9

end

That’s all the CPU-based core words, but there are still a bunch of OS-specific ones to look at, which get a little more interesting.

arm64_linux.cal

In os/arm64_linux.cal, we’ll find all of the words that interact with OS features, in this case using Linux system calls. Linux system calls on ARM64 are made using the svc #0 instruction. To specify the system call number, we store it in register x8, and arguments go in x0-x5. If a return value is provided, it will be in x0.

Since Callisto already supports Linux, this should be easy right? Just switch over the calling convention for the system calls, then the OS core is done! Unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple. The system call numbers are completely different between x86_64 and ARM64 Linux (and other architectures too), and some older calls that Callisto used on x86_64 were never implemented on ARM64.

Anyway, let’s see how a syscall works in practice with a simple example:

version Exit

func exit begin

__arm64_pop_x0

asm

"mov x8, #93"

"svc #0"

end

end

end

Words in the OS-specific core libraries are placed in version blocks mainly to document the feature flags they correspond with, as the backend should always enable these flags (or in more recent versions of Callisto, the core library itself enables them).

exit should simply stop the current program with a given return code, which we can use Linux syscall 93 (exit, unsurprisingly) for. Setting up the arguments can be done with the same inline functions as many of the other core words, then just select the syscall in x8 and execute svc #0.

Setup and Teardown

As mentioned in the backend part of this series, the backend expects an __arm64_program_init and __arm64_program_exit word defined. The state of the CPU when starting a program differs between operating systems, so this is the right place for those:

let addr __linux_argv

let cell __linux_argc

inline __arm64_program_init begin asm

"add x9, sp, #8"

"ldr x10, =__global___us____us__linux__us__argv"

"str x9, [x10]"

"ldr x9, [sp]"

"ldr x10, =__global___us____us__linux__us__argc"

"str x9, [x10]"

end end

inline __arm64_program_exit begin asm

"mov x8, #93"

"mov x0, #0"

"svc #0"

end end

program_exit is easy, because it’s just the exit syscall from before with a hardcoded return code. program_init’s code relates to retrieving command line arguments, so let’s get into that now.

Command Line Arguments

On Linux, command line arguments are passed into a program via the stack. On top of the stack is the number of arguments, followed by the address of each argument string.

Because one of the first things the compiler backend does is to move sp, program_init is used to save the number of arguments and a pointer to the argument array to some global variables for later.

What happens later? Not much. Getting the command line arguments using the globals doesn’t take much code at all:

version Args

func core_get_arg begin

8 * __linux_argv + @

end

inline core_get_arg_length begin __linux_argc end

end

core_get_arg uses pointer arithmetic to find the address of the string for a specific argument, and core_get_arg_length uses inline to directly compile to a global variable read.

Printing

Callisto’s only printing primitive is printch, which outputs a single character to the standard output. This isn’t particularly efficient considering most platforms have a way to send a much larger buffer to standard out at a time, but it works well enough right now.

On ARM64 Linux, syscall 64 is write, and it takes a file descriptor, a pointer to the data to write, and the number of bytes to write. Here, the file descriptor is always 1 (stdout), and the number of bytes is also 1. There’s no need to create a separate buffer for the data either, printch just adjusts the stack pointer and passes that as the address.

version IO

func printch begin asm

"sub x19, x19, #8"

"mov x8, #64"

"mov x0, #1"

"mov x1, x19"

"mov x2, #1"

"svc #0"

end end

end

Time

This is probably the OS function that needed to change most significantly when compared to its x86_64 counterpart. The x86_64 code used the time syscall to get a time_t value directly (a time in Unix timestamp format). This syscall does not exist on ARM64.

Instead, I had to write a new implementation using gettimeofday, which has a few new features compared to time, none of which I need here. It requires a pointer to a timeval struct, which stores both the time_t that Callisto uses and a microsecond count for much higher precision. It also supports a time zone argument, which the Callisto core won’t use.

version Time

struct __linux_timeval

cell sec

cell usec

end

Callisto’s struct syntax comes in handy here to define a struct with the right amount of space.

func get_epoch_time begin

let __linux_timeval tv

&tv

__arm64_pop_x0

asm

"mov x8, #169" # gettimeofday

"mov x1, #0"

"svc #0"

end

&tv @

end

end

The actual implementation reserves space using let, then passes its address as x0. After the syscall, the time_t value can be extracted from the local struct.

Files

Right, this is where things start to get complex. The first thing to do is define a whole lot of constants, plus a struct and some variables:

const FILE_READ 1

const FILE_WRITE 2

const SEEK_SET 0

const SEEK_CUR 1

const SEEK_END 2

const __linux_O_RDONLY 0

const __linux_O_WRONLY 1

const __linux_O_RDWR 2

const __linux_O_CREAT 64

const __linux_AT_FDCWD -100

const __linux_default_mode 0o666

struct File

cell fd

end

let File stdin

let File stdout

let File stderr

0 &stdin !

1 &stdout !

2 &stderr !

The constant definitions prefixed with __linux are for internal use, and I’ll explain them as they come up. The other ones (FILE_* and SEEK_*) are part of the Callisto file API, to indicate file mode and seeking mode. Also note the definitions of stdin, stdout, and stderr that allow all three standard I/O streams to be used as regular files, with the exact same API.

The bulk of the complexity in file support comes from open_file, which is responsible for connecting the Callisto file API to the Linux style one.

First up, we have to convert from a Callisto string to a null-terminated string. Callisto’s strings won’t have the additional space for a null terminator, so we’ll copy the data into a separate buffer. __arm64_memcpy shows up here, so the entire loop doesn’t need to be rewritten.

func open_file begin

let addr path

let cell mode

-> mode

-> path

let array 4096 u8 pathBuf

path Array.elements + @

&pathBuf

path @

__arm64_memcpy

Callisto also uses a completely different representation for the file mode, using one bit for read and another for write, so open_file needs to convert that to Linux-style RDONLY/WRONLY/RDWR. At the same time it adds the CREAT flag if necessary so that Callisto can make new files by writing to them.

let cell flags

if FILE_READ FILE_WRITE or mode = then

__linux_O_RDWR __linux_O_CREAT or -> flags

elseif FILE_READ mode = then

__linux_O_RDONLY -> flags

elseif FILE_WRITE mode = then

__linux_O_WRONLY __linux_O_CREAT or -> flags

end

It’s time to make the actual call and here again is a syscall that didn’t make it across from x86_64. On x86_64, open_file uses open, while on ARM64 it has to use openat (which is described in the same manpage). openat allows callers to specify how to interpret relative paths. To get the same behaviour as open I just pass AT_FDCWD for the additional argument, which tells openat to treat them as relative to the current directory.

__linux_AT_FDCWD

&pathBuf

flags

__linux_default_mode

__arm64_pop_x3

__arm64_pop_x2

__arm64_pop_x1

__arm64_pop_x0

asm

"mov x8, #56" # openat syscall

"svc #0"

end

__arm64_push_x0

end

Everything Else

The only things left are memory allocation and exception handling. I won’t go through their code in full, as they are basically a direct copy of the x86_64 version, with system calls updated for ARM64, but here are some interesting points about them:

Memory Allocation

- Memory allocation uses one of two different implementations depending on whether you compile with libc or not.

- If libc is enabled,

mallocandfreeare just pulled directly from there. - Otherwise,

mallocandfreeare naively implemented using themmapsystem call. While this call is definitely useful for allocating memory, it should be used as part of a more complete memory allocation system. Right now though, dynamic allocation is not common in Callisto code, so a sub-optimal implementation ofmallocisn’t the end of the world.

Exception Handling

- To support exceptions, the core library only needs define a function

__arm64_exception, which gets called for any unhandled exception. - The current implementation just prints the exception details, which sounds easy, except that the core library should not depend on the rest of the standard library…

- This is handled using a separate implementation of

printstrcalled__core_printstr, for the core library to use.

Linux ARM64 works!

Now, with all of the core functions implemented, all of the Callisto example programs compile and run correctly. During development I wrote a script to test this – it compiled a given program for both x86_64 and ARM64, then ran both resulting binaries (the ARM one via QEMU), and compared their outputs. This tool was very useful in ensuring that my new backend was completely compatible with the existing x86_64 one.

In the next and final part of this series, I’ll talk about the issues I faced when bringing all of this work over to macOS. Apple make some strange decisions in places, so getting everything working still took a little more work.

Comments

Please note: this comment system is experimental and may be removed.

Rules: Be excellent to each other!