A recent project of mine was to develop a simple graphical chat client for a simple new protocol that sprung up in the Uxn community. The protocol in question is Nanochat, and it’s so simple that you can even use it without a dedicated client at all!

Clients

Clients for Nanochat are easy to write, so it should be no surprise that there are already several to pick from.

Here’s a few of the options:

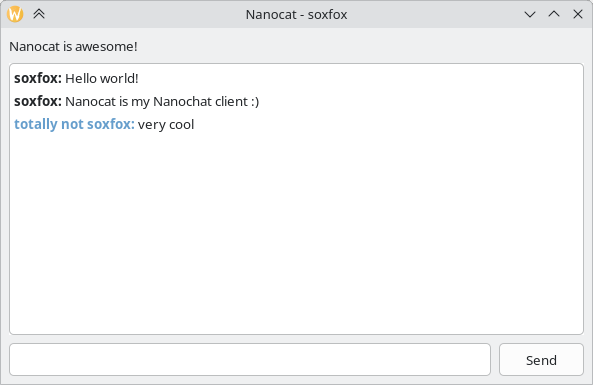

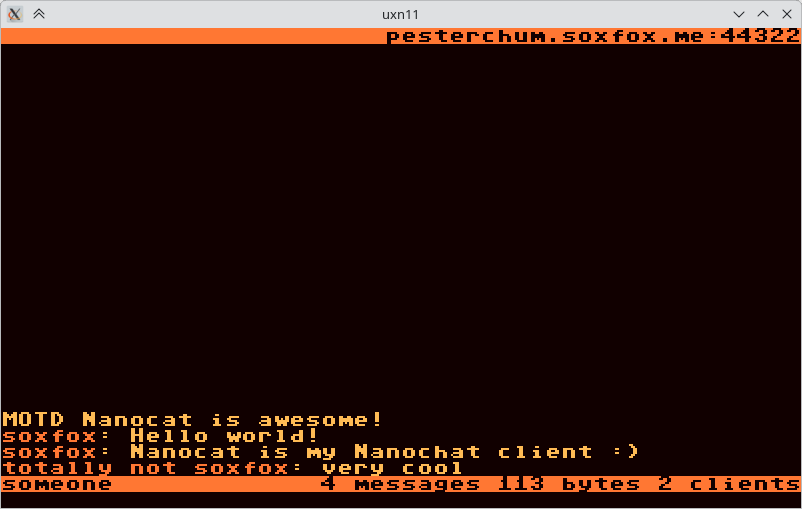

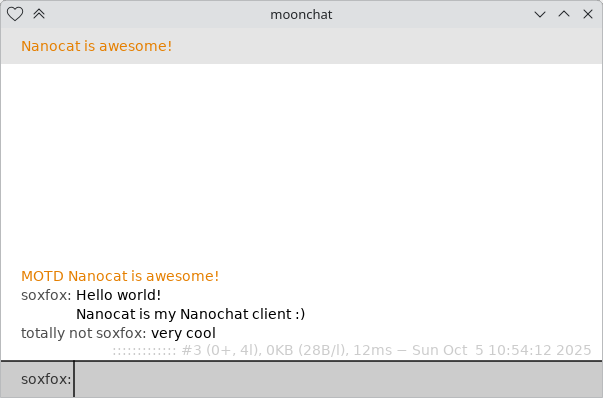

There’s my own Nanocat. d_m, who created Nanochat, wrote Electrum in Uxntal. Moonchat, by olive, is written in Lua using Love2D.

There are several others, written in various languages and using various toolkits.

The Protocol

I said you can use Nanochat without a real client, and it’s a great way to understand the protocol, so let’s do it! All that’s needed is a tool that lets you connect to a given TCP port and send and receive some text, like netcat. I’ll run a server, then in another shell session connect to it on the default port of 44322:

$ python serve.py

welcome to nanochat!

starting up with 2 messages (37 bytes)

client connected 127.0.0.1:35912

$ nc localhost 44322

Nothing gets received on the TCP socket yet, but that’s expected.

Every interaction with a Nanochat server involves one command being sent from the client, and one or more lines of response from the server.

Looking at the list of commands, we can see HIST, which should print out the entire message history:

HIST

2

a user: hi!

another user: hello there!

1

Ok, so we can see the messages, but what are the numbers above and below them?

The first number (2) indicates how many messages the server is going to send.

This makes it simple for the client to read the right number of messages – read the first line of the response as a number, then read that many additional lines, each of them being a message.

The final line is the index of the last message sent, which will be useful for some of the other commands.

When connecting to a large server, you probably don’t want to download the entire message history every time.

Nanochat has the LAST command for that reason.

LAST n where n is the number of messages you want to see will send only those messages:

LAST 5

5

a user: :)

soxfox: adding more messages

soxfox: because it makes this example better

totally not soxfox: wow! this chat is so real and active

soxfox: I know, right?

8

Great, that’s message history sorted, but what about sending messages?

That’s actually really simple, we just use the SEND command followed by the text of the message.

Nanochat doesn’t have a built-in concept of usernames, but the convention is to send all messages prefixed with a name of choice followed by a colon:

SEND soxfox: This is how you send a message

9

LAST 3

3

totally not soxfox: wow! this chat is so real and active

soxfox: I know, right?

soxfox: This is how you send a message

9

Perfect, the message was sent, and now appears in the history.

But what about receiving new messages?

How do we know when to ask the server for messages, and how many should we ask for?

The final two commands to look at are POLL and SKIP.

Like LAST, they take a number as an argument, but unlike LAST, that number is a message index (told you it would be useful!)

If we think back to before I sent that last message, the message index provided by the server was 8.

If another user wants to know whether any messages have been sent since then, they can use POLL.

It returns only one line: the number of messages after that index.

Users and clients can run POLL fairly regularly in order to discover new messages:

POLL 8

0

POLL 8

0

( I send a message now )

POLL 8

1

Once a client knows there are new messages waiting, it can send SKIP with the same message index to retrieve them:

SKIP 8

1

soxfox: This is how you send a message

9

And that’s it! Just five commands to handle message history, sending, and receiving messages. You could stop here, connect to a server with netcat, and chat to your heart’s content!

A Minimal Client

…or you could take everything you just learned and build an actual client program. I’m going to do just that, building a working client in next to no code. Rust is my language of choice here, but for a minimal command line client, all you need is a way to handle terminal input and output, and a way to connect to a TCP server.

This client really is going to be minimal. No fancy formatting, no /me or messages of the day, not even automatic polling. Now that your expectations are suitably lowered, let’s begin.

For configuration, I could build a stateful system that saves your preferred username and server, letting you change them at runtime and automatically loading them on startup… or I could just read command line arguments. That seems easier, I’ll do that:

use std::env;

fn main() {

// Read the configuration

let mut args = env::args().skip(1);

let username = args.next().expect("need username");

let host = args.next().expect("need hostname");

let port = args.next().unwrap_or("44322".into());

let port = port.parse::<u16>().expect("port should be an integer");

}

Cool, configuration done. Now let’s connect to the server:

use std::env;

use std::io::{BufRead, BufReader};

use std::net::TcpStream;

fn main() {

// Read the configuration

// ...

// Connect to the server

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect((host, port)).unwrap();

let mut reader = BufReader::new(stream.try_clone().unwrap());

}

Next I want to read the message history.

I’ll make a helper function to read messages from the server, as it will be useful for SKIP later.

Remember, the server’s response here starts with the count of messages, then that many lines, and finally the last message index:

fn read_messages(mut reader: impl BufRead) -> u64 {

// Read the message count

let mut buf = String::new();

reader.read_line(&mut buf).unwrap();

let count = buf.trim().parse::<u64>().unwrap();

// Read and print each message

for _ in 0..count {

buf.clear();

reader.read_line(&mut buf).unwrap();

print!("{buf}");

}

// Read and return the message index

buf.clear();

reader.read_line(&mut buf).unwrap();

buf.trim().parse::<u64>().unwrap()

}

We’ll call that in main:

use std::env;

use std::io::{BufRead, BufReader, Write};

use std::net::TcpStream;

fn main() {

// Read the configuration

// Connect to the server

// ...

// Get message history

writer.write_all(b"LAST 20\n").unwrap();

let mut last_index = read_messages(&mut reader);

}

$ ./client soxfox localhost

a user: hi!

another user: hello there!

a user: i like nanochat

another user: me too

a user: :)

soxfox: adding more messages

soxfox: because it makes this example better

totally not soxfox: wow! this chat is so real and active

soxfox: I know, right?

soxfox: This is how you send a message

Looks like the connection’s working, and the message history is coming back from the server. The last thing to implement is a main loop that can send and receive messages. As I said, this client won’t have automatic polling, and instead it will look for new messages every time the user presses Enter.

Here’s the main input loop, which displays a > prompt before reading each line.

use std::env;

use std::io::{self, BufRead, BufReader, Write};

use std::net::TcpStream;

fn main() {

// Read the configuration

// Connect to the server

// Get message history

// ...

// Process user input

print!("> ");

io::stdout().flush().unwrap();

let lines = io::stdin().lines();

for line in lines.map(Result::unwrap) {

// ...

print!("> ");

io::stdout().flush().unwrap();

}

}

And the logic inside is simple – send a message if the user entered one, and then read new messages.

Note that I’m not even bothering with the POLL message, SKIP alone is enough.

for line in lines.map(Result::unwrap) {

// Send non-empty lines

if !line.is_empty() {

writer

.write_all(format!("SEND {username}: {line}\n").as_bytes())

.unwrap();

let mut discard = String::new();

reader.read_line(&mut discard).unwrap();

}

// Get new messages

writer

.write_all(format!("SKIP {last_index}\n").as_bytes())

.unwrap();

last_index = read_messages(&mut reader);

print!("> ");

io::stdout().flush().unwrap();

}

That’s it! 45 lines of code, and you’ve got enough of a Nanochat client to connect to a real server and chat!:

$ ./client soxfox localhost

a user: hi!

another user: hello there!

a user: i like nanochat

another user: me too

a user: :)

soxfox: adding more messages

soxfox: because it makes this example better

totally not soxfox: wow! this chat is so real and active

soxfox: I know, right?

soxfox: This is how you send a message

> wow, so simple!

soxfox: wow, so simple!

>

someone: helllooooo!

>

What Next?

First off, you could make your own client, with whatever cool features and UI you like! Nanochat doesn’t stop here though, the community has come up with various conventions for additional features:

- Messages that start

MOTDare messages of the day, and many clients have a special area to display them. - Clients can send messages that don’t follow the

username: messageformat, which is commonly used to implement a/mecommand. - This is a fun one! Some clients interpret sequences like

\(...)as containing Sixel data, allowing inline images. - Replies to users often start with

username,to get their attention, and clients can choose to highlight these.

You could also go make up your own extensions to Nanochat and get your own little communities onto it.

But most of all, have fun with it! Feel free to come chat with us at vein.plastic-idolatry.com with whatever client you like :)

Comments

Please note: this comment system is experimental and may be removed.

Rules: Be excellent to each other!